This article was prepared within the framework of the RDI project CSO 2016-80158-R “La nueva emigación desde España: perfiles, estrategias de movilidad y activismo político transnacional” [New Emigration from Spain: Profiles, Strategies of Mobility and Transnational Political Activism], part of the State Programme for Research, Development and Innovation in Challenges Facing Society, financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (EDRF Funds).

1The global crisis has made Spain an interesting observatory from which to analyse migration patterns in times of economic crisis. During the years of economic expansion, before the crisis (2008), Spain led the European ranking in immigration (Domínguez-Mujica et al., 2014) thanks to the pull of job opportunities for immigrants in secondary-sector employment niches. However, the market for foreign workers was hit hard with the onset of a severe recession in 2008, and the disparity between the levels of wellbeing of the Spanish and foreign population grew significantly in the early years of the crisis (2008-2010) (Godenau et al., 2017). This triggered a considerable decline in immigration while also promoting re-emigration and the return of former immigrants.

2A second stage commenced in 2011 with what has been called the public or sovereign debt crisis, brought on by the fact that certain countries issued more bonds to finance their accumulated budget deficits. Containment of this deficit created tensions and problems between the Eurozone member-states that sought to keep it under control and the Southern countries which had incurred that debt. This situation gave rise to stringent austerity policies for Spain as well as Greece and Portugal. In line with those policies, the governments of these countries adopted tight budgets that caused public investment to contract and hit the self-employed and the middle classes very hard. It was during this second crisis period that emigration spiked among Spanish young adults, plagued by unemployment and the dearth of job prospects, especially in the most highly-skilled professions. As Pumares notes (2017, p. 134), “This second stage clearly affected young people who had finished their studies and were entering the market, but had no jobs to go to, as well as young people who had begun to work, but because they had been with their companies a short time, were the cheapest to dismiss when adjustments were made”.

3However, eight years down the road, it is necessary to determine whether or not the migration trends of this second stage are changing as the Spanish economy begins to show signs of recovery – still incipient at best – and how emigration processes are intertwined with returns and re-emigrations at the dawn of a post-crisis era. There is solid evidence of a higher mobility level, typical of today’s more complex and less predictable world. This in turn reveals the obsolescence of the old emigration patterns that formerly characterized Southern European countries, which reversed their net flows at the turn of the century and thus effected a migration transition.

4In order to address this idea, in this paper we use different procedures to measure data obtained from sources at the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) and the Spanish Ministry of Employment and Social Affairs and present the results in graphics and tables. The structure of this study is as follows. Firstly, it describes the state of the art in research on the correlation between the economic crisis and the recent emigration of Spanish citizens. Secondly, it presents the sources and methodology used in this research. The third chapter discusses mobility indicators during the crisis years and the early post-crisis period. Fourthly, it analyses the geographical aspect of this phenomenon, i.e. how crisis and post-crisis situations are related to the Spanish diaspora and its consolidation. Finally, the paper summarizes the most relevant discoveries made in the course of our research.

- 1 We limited this category to Spanish citizens born in Spain to exclude processes of re-emigration or (...)

- 2 The correlations between economic and emigration data are based on the two years after the beginnin (...)

5As stated above, the decline in immigration, the recommencement of Spanish emigration and the new profile of emigrants, contrasting with that of the last major wave of outbound Spaniards (1960-1973), can be linked to the crisis’s severe impact on countries in the weak European periphery (King, 2015). Consequently, the economic austerity measures implemented during the hardest years – from the debt crisis (2011) onwards – and their budgetary effects triggered a surge in the emigration of Spanish youth and young adults (25-34 years old),1 as the outflow figure registered two years later clearly shows2 (Table 1).

Table 1. Correlation between statistical indicators on unemployment and emigration.

|

Unemployment rate of young adult (25-34 yo) Spaniards

|

|

Outflows of young adult (25-34 yo) Spaniards abroad

|

|

2009

|

17.97

|

2011

|

12,302

|

|

2010

|

20.60

|

2012

|

11,367

|

|

2011

|

21.74

|

2013

|

13,919

|

|

2012

|

25.41

|

2014

|

16,068

|

|

2013

|

27.40

|

2015

|

19,694

|

|

2014

|

25.37

|

2016

|

16,413

|

|

Pearson: 0.92

|

Sources: National Accounts. Working Population Survey. Migration Statistics. INE

6This migration process has attracted a great deal of attention from the Spanish academic community, as attested by the abundant literature published on the subject (López D., 2010; Reher et al., 2011; Arango et al., 2014; Navarrete, 2014; Domingo & Blanes, 2015; López-Sala & Oso, 2015; Pumares & González, 2016; Domínguez-Mujica et al., 2016, etc.). The emigration process has also received wide media coverage, generating numerous journalistic articles and other forms of social communication on the topic (Díaz-Hernández et al., 2015; Díaz-Hernández & Parreño-Castellano, 2017).

7Beyond Spain’s borders, the socio-demographic and geo-demographic parameters of this process have also been analysed by other researchers, who link it to the migration behaviour of Southern European countries during the crisis (Herm & Poulain, 2012; Glynn, 2014; Triandafyllidou & Gropas, 2014; Fonseca & McGarrigle, 2014; Recchi & Salamońska, 2015; Montanari & Staniscia, 2017, Domínguez Mujica & Pérez García, 2017, etc.). In their interpretation of this emigration stage, said authors point to the role of educational and professional backgrounds as well as the truncated ambitions of future employment for these young people, whose families had focused their financial efforts and pinned their hopes on the upward social mobility of their descendants (Parreño-Castellano et al., 2016). As a result, the mass media has presented emigration as a loss of social success for middle-class families, whose destiny was envisioned quite differently in the collective Spanish mind. They have also examined these emigrants’ political disaffection and feelings of anomie with regard to the economic and social situation in Spain, due to a perceived deterioration of the standards and ethics of social coexistence (King et al., 2014; Bygnes, 2015).

8At the same time, migrants have created a new framework of political participation based on a new form of migrant associationism, developing political strategies and practices in communities that overflow national borders (such as Marea Granate, Oficinas Precarias, etc., in Spain’s case) (López-Sala, 2017) and, paraphrasing Levitt (2001, p. 203), occasionally coalesce into diasporas if a “fiction of congregation” takes hold. Social media and ITC have made it easier for young people to receive information on events, trends and culture in real time, giving rise to new forms of communication among migrants and between them and the societies to which they belong (Koikkalainen, 2012).

9From this perspective, the tendency of researchers to focus on the emigration of skilled individuals is hardly surprising. The global trend of an unprecedented increase in the flow of skilled migrants is accompanied by rising intra-European mobility, fostered by the European Higher Education Area, university student exchange programmes (Erasmus, Leonardo da Vinci, etc.) and the European Job Mobility Portal (EURES). The idea that “migrating to learn can mean learning to migrate” (Li et al., 1996) suggests that student mobility (graduates and post-graduates) is an integral part of transnational migration systems, whose networks have paved the way for the current circulation of skilled labour (Findlay et al., 2017; Glorius, 2017).

10The aforementioned characteristics make it clear that the outbound migration of Spanish nationals after the crisis requires new and different explanations for an equally different social phenomenon. The most suitable theoretical framework for interpreting this process is that of the “mobility turn” (Urry, 2000; Kaufmann, 2002; Montanari, 2005; Cresswell, 2006; Kellerman, 2006; Sheller & Urry, 2006; etc.), which argues that greater attention should be paid to flows than to points of origin or destination, for the direction and speed of mobility processes are more important than the destinations themselves, and mobility barriers, though they do exist, have cracks that cannot be ignored (Montanari & Staniscia, 2016). This conceptual approach is appropriate for the unstable world of the new century, marked by the globalization of production and consumption and new forms of economic integration and social conduct.

11Finally, when analysing this process from a long-term perspective, on the verge of economic recovery, it is even more essential to examine the new emigration stage from the angle of human mobility, as King & Christou (2011) precociously suggested with regard to return migrations, as residing or being in a certain place is an intermittent phenomenon that interacts with other types of connection and communication processes. Therefore, according to Cresswell (2006), mobility must be considered not only as an empirically observable phenomenon but also as an ideological concept synonymous with freedom, transgression, creativity, life itself and embodied experience. This may well be the most accurate interpretation of the recent emigration trend and its attendant return and re-emigration processes, for they clearly evidence a genuine tension “between mobility, on the one hand, and a search for a stable home(land) in which to settle and ’belong’ on the other” (King & Christou, 2011, p. 454).

12Any quantitative analysis of Spanish emigration must rely on data obtained from the sources offered by Spain’s National Statistics Institute on Spanish population stocks abroad and on outflows and inflows. In order to provide a comprehensive overview of these quantitative data on the emigration of Spaniards, we have condensed the available information and its sources in Table 2.

13Nonetheless, we are aware that there may be gaps in this information due to the under-registration of emigrants who have failed to complete bureaucratic formalities (Romero-Valiente, 2016), particularly among Spaniards residing in a European Union country that does not require them to obtain work permits, those planning to stay abroad for less than one year, or those living as undocumented immigrants and waiting to regularize their status. In many cases, formal registration is also delayed because migrants are unsure of their future plans.

Table 2. Statistical information from Spanish sources.

|

Data on population stocks

|

Consular registration records from the Deputy Directorate of the Ministry of Employment and Social Affairs

|

|

Census of Spaniards Residing Abroad (PERE-CERA) from the National Statistics Institute (INE)

|

|

Data on outflows and inflows (expressed as microdata)

|

Residential Variations Statistics (EVR) from the National Statistics Institute (INE)

|

|

Migration Statistics (ESMI) from the National Statistics Institute (INE)

|

Created by the authors

14In terms of methodology, we evaluated the statistical information as a whole and segmented by age group, nationality, source country and host country. Additionally, we calculated different rates (net and gross migration, emigration and return rates) and standardized statistical data when necessary.

15Special mention must be made of the analysis of return flows. As Whaba (2014) rightly points out, return migration is difficult to measure, and although this is usually achieved by relying on the out-migration statistics of host countries and longitudinal surveys, in this case we have used data on inflows of Spanish citizens born in Spain who re-register as residents in Spain after formally registering the end of their residency in a foreign country (Residential Variations Statistics). Therefore, our return calculations are not based on a universe of migrants, which could have been evaluated by cohorts and time of residence abroad; rather, they reflect the dimension of return flows in relation to emigration flows and their evolution over time.

16As for economic indicators, these were obtained from the Working Population Survey and the National Accounts (GDP), as supplied by the National Statistics Institute.

17The quantitative analysis of these data explains the evolution of stocks and flows of Spaniards abroad since the crisis began, providing deeper insight into the changes in migration patterns during two different stages: the years marked by the financial and debt crises and their consequences, and the new situation of the incipient post-crisis period (2015-2016).

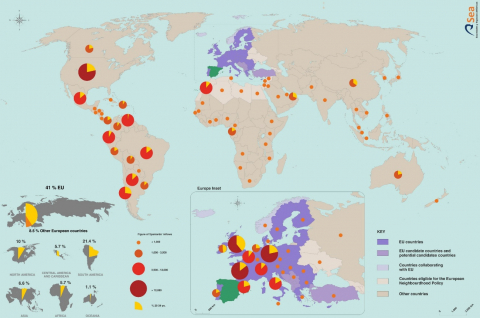

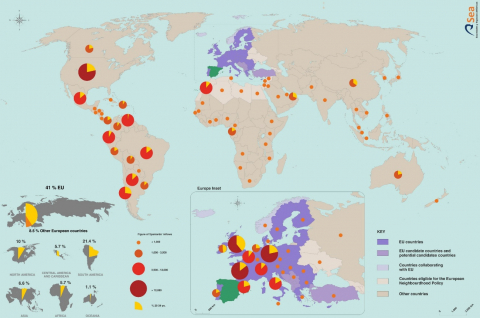

18Finally, all data have been geo-referenced to produce a digital map (ArcGIS) that facilitates a clear geographical interpretation of the results, indicating the outbound and return destinations of Spanish emigrants as well as the geographical variations observed for the study period.

19Inflows and outflows of young adult Spaniards have varied over the past decade. As shown in Figure 1, during the economic boom period and the early years of the crisis, outflows remained stable. Starting in 2011, with the introduction of measures to combat the debt crisis in Spain, outflows registered a steep, nearly linear increase that did not lose momentum until 2015. Since then, as the economy has improved, we observe a decline in outflows. The lack of more recent data makes it impossible to conclusively identify 2015 as a turning point in the period analysed. With regard to inflows, these exhibited a gradual downward trend during the 2005-2013 period with only a few minor inter-annual increases, largely owing to the statistical relationship between outbound and return flows. In 2014 the return numbers began to rise, due partly to the increase in outflow data and partly to the improving economic situation; as a result, in 2016 returns increased despite the drop in outflows.

Figure 1. Outflows and inflows of Spaniards (25-34 yo) abroad.

Source: Residential Variations Statistics, INE

20Overlooking the statistical dependence of both variables, the crisis brought an increase in outflows and a stagnation of returns, while the post-crisis shows a decline in outflows and a rise in inflows. The latter statement is confirmed by other indicators, such as the ratio of the total Spanish population residing abroad (PERE) (Table 3).

Table 3. Return rate in percentages.

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

2.15

|

2.03

|

1.98

|

1.52

|

1.40

|

1.68

|

2.02

|

2.44

|

Source: Census of Spaniards residing abroad, INE

21From a structural perspective, the evolution of Spanish migration figures in the crisis and post-crisis years is related to economic parameters. We can see a significant correlation between the evolution of GDP and emigration data, and between the time series of unemployment in Spain and return data. This correlation is especially strong if we consider that it takes about two years for mobility figures to reflect trends in the behaviour of economic data, as noted earlier. Unemployment benefits, family support, the underground economy, etc., are factors that delay mobility for financial reasons, whereas migratory success, even if only partial, tends to delay return processes. Therefore, the correlation between GDP and emigration figures for Spaniards between ages 25 and 34, factoring in a two-year time lag between the series, is inverse and quite strong, as shown in Figure 2, where the trajectories of the two variables practically mirror each other. The same is true of the correlation between the unemployment rate for young adults and the migration rate of this group, as illustrated in Figure 3, but in this case with a direct least-square coefficient.

Figure 2. Correlation between GDP and emigration.

Sources: National Accounts. Migration Statistics. INE

Figure 3. Correlation between unemployment and emigration.

Sources: Working Population Survey. Migration Statistics. INE

22Both graphs clearly show that GDP and unemployment evolved differently during the crisis and post-crisis periods, with 2013-14 being the turning point. On a macroeconomic scale, that moment marked the beginning of a timid recovery. The turning point for migration flows came later in 2015-16, when upward GDP and downward unemployment appear to align with mobility data.

23The crisis and post-crisis periods exhibit different trends not only with regard to inflows and outflows but also in terms of the total mobility and net migration of young adult Spaniards. The evolution of the gross migration rate, understood as the sum of all migratory movements, points to steadily rising mobility: more movements in every direction. Based on data on the foreign migration of Spaniards (INE) and the Spanish population, the gross migration rate for Spaniards was, by our own calculations, 1.20 per 1,000 people in 2008; 1.48 in 2012 and over 2.55 in 2016, which seems to confirm a new tendency towards higher mobility. However, if we observe the evolution of gross and net migration, we see that mobility increased during the crisis, and it is only now, in a recovering economy, that both indicators have begun to drop (Figure 4); we are entering a period of lower mobility among young adults thanks to the decrease in outflows and because returning home tends to become more important to migrants later in life (ages 35-39) as the years begin to weigh on them.

Figure 4. Evolution of gross and net migration of Spaniards (25-34 yo).

Source: Residential Variations Statistics, INE

24In contrast to the predominant emigration of young adults during the worst years of the crisis, we are now entering a new and as yet undefined period that will alter the composition of migration flows. It seems clear that the traditional model of migrations in Southern European countries no longer applies to Spain at this juncture; we are now facing a more complex situation of pendulum migration, in a scenario of fluid, intermittent migration processes typical of the paradigm of human mobility.

25To this we can add data provided by the INE on the bio-demographic composition of inflows of Spaniards from foreign countries. This complementary analysis sheds light on the trends observed in 2015 and 2016, which show signs of an incipient pattern change corresponding to the early stages of economic recovery (referred to here as the post-crisis period), with indications of pendulum mobility, return, circularity and re-emigration.

26The data on Spanish inflows from abroad (Figures 5 and 6) for two different years, at the beginning of the emigration stage (2009) and the dawn of the post-crisis period (2016), reveals a remarkable change in the ages of people on the move. In 2009, the two main groups were adult and elderly migrants – the latter remnants of the emigration wave in the 1960s and 1970s – but in 2016, the generally increasing inflows (the absolute figures allow us to identify this phenomenon) included a surprising number of children, many of whom may be predisposed to emigrate when they reach young adulthood. In other words, in 2016 we begin to see a decline in the number of incoming retirement-age Spaniards and a return phenomenon dominated by young adults and adults with children, many of whom were born in Spain.

Figure 5. Inflows of Spaniards from abroad. Structure by age in normalized data (2009).

Source: Residential Variations Statistics, INE

Figure 6. Inflows of Spaniards from abroad. Structure by age in normalized data (2016).

Source: Residential Variations Statistics, INE

27In summary, given the quantitative importance of inflows and outflows and their structural differences by age, we can make out two sets of migration patterns, one during the crisis and another in the post-crisis period. If the trend is ultimately confirmed, there may be more returns in coming years, but this inflow will not resemble that of previous decades, dominated by former emigrants past retirement age. Furthermore, the scenario that determines migrations has changed: great strides have been made in the creation of global markets, in corporate internationalization, in the qualification of the young adult population, in interconnectivity and accessibility, in the frequency of student and tourist travel (which increases the likelihood of future job and residential mobility) and in the activation of contact networks that facilitate inter-migrant community support. Thus, we are almost certainly moving towards a higher, less unidirectional standard of mobility, different from the one that defined the years of prosperity and crisis in Spain at the turn of the century.

28We need to identify and confirm the patterns of migration expressed in space and time; in other words, to see if the ties between countries and societies that defined Spain’s migration history still exist, or if there are changes that indicate a division between the aforementioned crisis and post-crisis periods. In order to do so, we must consider a number of factors: the economic conditions in host countries, as well as the economic situation in Spain; corporate internationalization and the creation of transnational market structures; the laws and regulations of the European Union and other states; the globalization of job markets for skilled migrants; post-colonial ties; etc.

29Figure 7 shows the outflows and Figure 8 the inflows for the last eight years (2009-2016). The first map shows that the largest outflows are to Western Europe and the Americas, although secondary flows extend to most of the world’s countries. As illustrated below, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the United States and Switzerland, along with Ecuador, are the main host countries, with other EU states and Latin American countries in second and third place, respectively.

Figure 7. Outflows of Spaniards (emigration) 2009-2016.

Figure 8. Inflows of Spaniards (return) 2009-2016.

The circles correspond to the total groups of migrants and the yellow segments to those between 25-34 yo.

Source: Residential Variations Statistics, INE

30However, if we consider the proportion of young people to total outflow by country, we notice several differences that reveal the influence of unique pull factors on young adults. In Ireland, Austria, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, China, Australia, Norway, Chile, Canada, France, the United States and Switzerland, young adults represent a very high percentage of outflows, indicating strong work-related pull factors. A healthier economy and a job market where skilled professionals are in demand have been decisive factors in determining the direction of outflows, and another is the Spanish economy’s own internationalization process, with important companies operating in the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Australia, Canada, the United States, Saudi Arabia, China, Chile, Panama, Peru and other countries. Yet young adult Spaniards account for a small fraction of the outflows to Latin American countries like Ecuador, Venezuela, Argentina or Colombia, as these trends largely correspond to the second-generation descendants of past immigrants (from Ecuador, for instance) or flows related to historical pendulum migrations (e.g. with Venezuela and Argentina).

31If we consider the distribution of young adult (25-34 years old) emigration by host country for both periods, we find that the five countries mentioned above (United Kingdom, Germany, France, United States and Switzerland) absorb over half of all outflows in both the crisis (2009-2014) and post-crisis period (2015-2016), accounting for 56.5% and 58.6% of movements, respectively. Additionally, the majority of all other movements in both periods were headed for other EU countries and Latin America, with the exception of China and a few Gulf nations.

32Although the distribution of flows in the two periods presents no significant differences, there are some details worth mentioning. While the relative importance of Great Britain, Germany and Switzerland in outflows is rising steadily, all other Western European nations have lost ground, with the exception of Denmark, Sweden and Poland. Outside the European Union, the numbers for almost all countries – excepting Chile, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Japan – have declined. It is also interesting to note the relatively diminished flows to the United States, Brazil, Argentina and China. This can be explained by changes in economic situations and migration policies.

33Naturally, since emigration is a precondition for return, the same geographical areas are affected by return movements of young Spaniards. The majority come from the United Kingdom, France, Germany and the United States. In the cases of Switzerland, France and Germany, the volume of inflows is relatively lower than the ratio of outflows to total inflows. The opposite is true of those returning from Ireland, China, Portugal, Morocco, Brazil and Argentina, all countries that maintain a higher gross migration rate.

34These disparities between outflows and inflows force us to calculate the return rate for each period, which we have done for countries with a gross mobility greater than 0.7 percent. For the 45 countries we analysed (which together account for 93.6% and 95.4% of gross mobility in each period), the average return rate was 29.7% during the crisis and 34.5% in the post-crisis period; in other words, approximately three out of every 10 young people who emigrate abroad have returned in the last two years.

35In the incipient post-crisis era (2015-2016), nearly all countries register more returns (primarily due to less outflow), but return rates from Latin America are much higher than in the previous period, especially in the cases of Venezuela, Ecuador and Brazil. This geographical trend seems to indicate that many Latin American countries were “safe haven” destinations for Spanish emigrants during the worst years of the crisis, especially when their economies needed skilled professionals (Brazil until 2013, Ecuador hiring Spanish doctors for its universities, etc.), and lost that status once the economic situation in Spain started to improve. These types of migration relationships reinforce post-colonial ties (Avila-Tàpies & Domínguez-Mujica, 2015), the full significance of which is revealed if we consider the investments of Spanish companies in those countries or the flow of Latin American emigrants towards Spain. In contrast, returns increased less in the case of certain European Union host countries (Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Italy and Portugal) as well as the United States, Mexico, Japan, Andorra and the Philippines (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Return ratio (2009-2014/2015-2016) and return trends for Spaniards (25-34 years old).

36This paper has analysed the international mobility of young adult Spaniards since 2008, generally considered the end of the period of economic prosperity which Spain had enjoyed since the turn of the century. With the onset of the public debt crisis in 2011, the already battered Spanish economy was plunged even deeper into recession, and the first obvious signs of an increase in migration outflows appeared. Consequently, the decline in immigration and the return and re-emigration of existing immigrants was compounded by the emigration of native Spaniards, especially young adults between ages 25 and 34. These outflows continued to rise until 2015 because, as explained above, it takes about two years for migration figures to reflect trends in gross domestic product and unemployment due to various factors (family support, existing savings, unemployment benefits, etc.) that qualify the temporal relationship between the economic situation and international mobility.

37Until 2014, inflows or returns of young Spaniards remained stable, but in 2015 and 2016 signs of change indicated that the economy and job market were starting to bounce back, and migration patterns began to change as well. Not considering the problem of under-registration, statistical data points to new trends that will have to be confirmed in the coming years. In 2015 and 2016 total and young adult emigration flows began to slow down, returns increased slightly – although the increase is less noticeable among young adults and more so when we look at total volume – and both gross and net mobility rates went down.

38To this we must add a change in the structure of returnees by age. At the beginning of the crisis, as in years past, returnees were predominantly adults between the ages of 25 and 39, and the second largest group consisted of people aged 60 to 69 who had emigrated decades earlier; however, in the recent period of economic recovery, returnees are usually adults between 30 and 44 years old, often accompanied by children between ages 5 and 14, and the flow of retirement-age returnees has lessened.

39Based on these data, it is our conclusion that the international migration patterns being recorded in the recent post-crisis period are different from those of the crisis years, although this will have to be confirmed as the economy continues to recover.

40From a geographical perspective, and saving potential distortions due to the economic circumstances of each country and changes in national migration policies, the migration of young adult Spaniards exhibits a territorial behaviour that is the product of six main factors: the creation of a common economic area in Europe; the economic internationalization of Spanish companies; the creation of a global job market for skilled workers, affecting more and more countries; the growing power of new economic hubs across the globe; and the existence of post-colonial and cultural ties to Latin America. This explains why, in both periods, the most significant flows are to/from countries in the European economic area, and why there are also relevant flows to/from other economic areas such as the United States, Australia, China or countries on the Middle East.

41However, in the early years of economic recovery, outflows to Latin America have decreased and returns from that continent have increased; this translates into stronger migration ties with European Community countries and others whose job markets have a need for skilled young adults (Switzerland, the United States, Australia, etc.), even though the return rate has risen slightly due to the decrease in outflows. This paints a picture of Latin America as a “safe haven” job market, which made it a sensible option in the worst years of the crisis thanks to post-colonial relations and cultural ties.

42In addition, we must also consider the steadily rising return rates from other countries like China, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. All of this information allows us to deduce that, when it comes to mobility, young Spaniards in the post-crisis period prefer European Union states and other developed countries in the English-speaking cultural and financial world (United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, etc.) within the global market for highly skilled professionals.

43We must not overlook another geographical peculiarity that characterizes the mobility of young Spaniards in both the crisis and post-crisis periods, manifested in the high emigration and high return rates that mark Spain’s relationship with certain neighbouring countries. This is particularly true of Morocco, Portugal and Andorra and points to a generalization of international pendulum movements that further complicates the migration panorama, sketching a more complex global scenario where new processes of fluidity and intermittence, typical of the paradigm of human mobility, interact.

44In short, we believe that there are two different sets of migration patterns for young Spaniards, one for the crisis years and another for the post-crisis period, although the latter will have to be confirmed as the process of economy recovery continues. In any case, the current situation differs from that of the prosperous years around the turn of the century (1998-2008); mobility today is more important due to the increasing number of skilled young Spaniards who choose to enter the global (and specifically the European) job market, especially if we bear in mind that Spain’s economic restructuring process was achieved by cutting wages. In this situation, the skilled migrant, if not the expatriate, carries more weight than in the past, implying that Spain has a new role to play in the international economy.