- 1 For a general picture of the post-Communist transition 25 years later, see Roaf et al. (2014), and (...)

1In the past quarter of a century since the fall of Communism, not only the evolution of the state and its functions, but also the ideas about the state/government’s role, has gone through serious transformations in several stages.1 From “everything is state” during the Communist period, there was an attempt at radically reducing the state presence and discretion. Liberal economists tried to promote the idea of minimal government participation in the economy. But in reality, all theoretical controversies primarily concerned vested interests and the battle for economic power. Conflicts of interest were served by economic discourse and different ideological paradigms. The structure and dynamics of public and private debt offer a clear illustration.

2The relationship between ideas, interests and institutions lies at the heart of old academic debates with no clear solutions (there is abundant political science literature concerning these questions, but economic studies are relatively rare; see Hay, 2004, Rodrick, 2013, Marques Pereira and Miguel, 2015). This article endeavours to retrace and analyse the main trends in the state/government’s role in the economy and the debt trajectory in the Balkan countries in the period 1990-2013. We look at two groups of countries: primarily Bulgaria and Romania (EU members since 2007), but also Albania, Serbia and Macedonia (currently at different stages of negotiations for EU accession).

3In short, behind the different theoretical models about the place and functions of the state/government, expressed by leading actors and defended in the public sphere, there lay a hidden struggle of actors’ interests to dominate and capture the transition process and the post-Communist transformation. Analytically, we define two co-existing processes; one dominates the other at different periods: (i) the state capture process, and (ii) the inverse process of de-capturing, i.e. of state normalisation. One of our hypotheses is that the theoretical models and ideas, as well as the general economic discourse, while possessing relative autonomy, were mainly aimed at justifying actors’ interests and bolstering acceptance by the broader public.

4The first period started after the collapse of the planned economy (and in some sense had been prepared beforehand, in the already-stagnating planned economy). This period was characterised by primitive accumulation of capital and privatisation of public, “all-people’s” property. We call this the “state capture period”. In this period, we observe the conversion of power endowments from the old administrative system into monetary and capital resources, typical of the capitalist economy. The forms of this conversion varied significantly. These concerned the various privatisation mechanisms (tenders, privatisation vouchers, sales to foreigners, etc.), clear or “ambiguous” appropriation of public property (so-called “input – output draining”), and various methods of depreciation, and later transfer, of assets and liabilities. Within this large-scale redistribution process, the state/government was a leading transmission mechanism. It served the interests of various groups, mostly the old Nomenklatura, as well as some newly-established actors. During this period, the discourse on private property, on the benefits of privatisation, on the efficiency of price liberalisation – in short, the liberal ideas of pure, efficient markets – were adopted and became widespread.

5The logical end of the aforementioned dynamics was massive public debt, followed by financial and banking crises, inflation and hyperinflation. This sequence was present in all the former Communist countries. The crisis in the aforementioned “crony” period occurred around 1996/1997.

6Immediately after the crisis, when the redistribution process was approaching an end, the second period started. This was a period of a certain degree of de-capturing and normalisation. Interests groups appeared that tried to stop the crony processes, and to restore the normal, public functions of the state (in line with the EU criteria for good governance, and good public practices). In other words, various mechanisms of “liberating” the state from crony groups and establishing a “normal state” emerged. In this period, tackling debt, applying fiscal orthodoxy, and establishing clear policy rules became not just political priorities, but also firm principles of economic theory.

7This state normalisation occurred through two main mechanisms. The first had a more or less internal, domestic dimension, and consisted of choosing and establishing a credible monetary regime. Two types of monetary reforms, or monetary anchors, were implemented: (i) an externally-oriented monetary regime (Avramovich’s monetary system in Serbia, Bulgaria’s Currency Board Arrangement, and Montenegro’s unilateral adoption of the euro), and (ii) an internally-oriented monetary regime (inflation targeting in Romania, Albania and Macedonia). The second main mechanism for limiting state capture was the EU anchor (accession to the EU as a civilisational and geopolitical choice). In the case of Bulgaria and Romania, the chronology breaks down into two sub-stages: (i) pre-accession and (ii) full EU membership. Later, full membership weakens the general functions of the state, which to some degree becomes again an object for serving different group interests (the mechanisms will be explained below). This chronology is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Chronology of the Transition and Role of the State

8The structure of this paper follows the chronology of the transition: in Part 2, we outline the first years of the transition, the state capture, and the 1990s crisis. Then in the Part 3, we present the two main anchors of stabilisation: the monetary regime and EU membership.

9Twenty-five years after the crisis of the socialist economies in the Balkans, the main particularities of the first decade are now increasingly clear. At that time, these specific features were difficult if not impossible to see because emotions ran high and the environment was very dynamic/unstable. Societies were seized by alternating waves of enthusiasm and disappointment, but as a whole, the general feeling was that Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries were moving to something new: to a social and economic system that would eventually bear fruit.

- 2 In reverse order – for the socialist primitive accumulation, resources should be confiscated from t (...)

- 3 Some researchers go further and interpret the collapse of the Communist system as deliberately plan (...)

10With the passage of time, it has become clearer that the early years were characterised by a primitive accumulation of capital and property, massive wealth redistribution, and the formation of a new capitalist class. Processes of a primitive accumulation of capital, well described by Karl Marx (in Chapter 24 of Capital), as well as by Evgeni Preobrazhensky (primitive socialist accumulation in his New Economy)2 were non-market by nature. They were political and administrative processes, leading to a mass conversion of power resources and positions of the old Communist Nomenklatura into monetary and property capital.3 In this respect, János Kornai’s description of the elites and players in the transition is quite clear:

11Birds are sitting in a tree. A gun goes off. They all fly into the air, and then land again. Each bird may be on a different branch, but the whole flock is back sitting in the tree again. (Kornai, 2000).

- 4 There are many publications, such as Olson (2000), Sonin (2008), Wedel (2003), Pejovic (2003), Olei (...)

12In attempting to summarise this initial period (from the end of the totalitarian system to the crisis in the second half of the 1990s), economists usually speak of the “privatised state”, “private state”, “crony state” (also used are terms such as “crony transition”, “cronyism”, “grabbing hand”, etc.).4

13Obviously, one can argue over the reasons behind the extremely corrupt cronyism that arose as the planned system broke down. However, one thing is clear – in that giant process of redistribution of resources and wealth, the government played a leading and instrumental role. Due to its hypertrophy during the socialist period and its key place in the planned economy, the state was a perfect tool and object itself for this massive redistribution and accumulation of capital. The mechanisms of privatisation and plundering of state enterprises have been documented and analysed extensively in the literature (Volkov, 2005; Bundjulov and Chalukov, 2008). As an example, we could cite the “input–output privatisation”, a term introduced by V. Antonov (1995). This term mainly means that the different legal or illegal crony structures channelled sound assets (e.g. machines, raw materials or final products) to themselves, leaving the bad assets and all accumulated losses in the public entity. The public entity was financed by the budget, and ultimately covered by the money supply, insofar far as the Central Bank was directly subordinated to the government (through the Ministry of Finance).

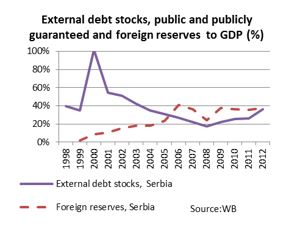

14As a whole, during this crony phase of the post-Communist transformation, the public and quasi-public debt snowballed (in most countries, except in Romania, high external debt has been a legacy of the Communist era). Budget deficits increased substantially. Conversely, the banking system and the Central Bank became a logical transmission mechanism. Losses were generated not only in the public sector and in state-owned banks, but also in the newly-created private-sector and crony banks, which accumulated significant amounts of non-collectible claims. Inevitably, this process eventually reached the Central Bank, which socialised the losses and theft by monetising them, i.e. by increasing the money supply (see Berlemann and Nenovsky, 2004, for the Bulgarian case). Overall, the bandit privatisation logically led to an accumulation of public debt (because the losses were transferred to the public sector, whereas the benefits went to the newly-created private one). While the redistribution took place at full speed, the disorganisation and declines in production were impressive (see macroeconomic indicators in Appendix 1). For example, GDP declined by more than 10% for the first few years in Bulgaria and Romania, and by more than 30% in Albania and Serbia. Public finances deteriorated rapidly, and the money supply and inflation exploded. Non-performing loans surged to historically unprecedented levels.

15Now, as time has gone by, it is possible to argue that there was a considerable lack of structural reforms (although some politicians claimed that they had made such reforms). The public witnessed numerous theoretical disputes with policymakers and politicians, who tried to convince public opinion. But in fact these disputes, or discourses, were a disguise for group interests. Entirely in the Marxist logic (and contrary to the views of Keynes), the ideas and theoretical models of reforms were subordinated to private and group interests. Although the economic literature argued about the sequencing of different stages of reforms (liberalisation, restructuring, labour market flexibility, institutional building, etc.), these theoretical discussions were secondary in nature or were aimed at diverting attention away from the real goal – redistribution of income and wealth, the formation of new capitalists.

16Of course, the economic problems also coincided with the specific political situation for each country. For example, the financial crisis in Yugoslavia and Montenegro concerned the processes of their political collapse (Mladenovic and Petrovic, 2000, Fabris et al., 2004, Schobert, 2003). In Albania, the 1997 crisis was related to the incredible surge, then later crash, of financial pyramids. The country’s main political and economic figures were involved in the emergence of these pyramids (Jarvis, 2000).

- 5 See also Ignatiev (2005), Nenovsky and Rizopoulos (2003, 2004), Dobrinsky (2000).

17In Bulgaria, the crisis in the late 1996 and early 1997 was one of the deepest in Eastern Europe, characterised by enormous destruction of income and wealth. It led to a demonstrative and radical change in the monetary regime and to a de facto refusal of active monetary policy. This was symbolised by the introduction of a Currency Board, where by definition no monetary policy is permitted (Berlemann and Nenovsky, 2004).5 In 1997, a crisis also broke out in Romania, where political power changed hands (as in Bulgaria). Right-wing politicians came to power, supported by the international financial organisations and foreign capitals (Nenovsky et al., 2012).

18As already stated, the ideas served the interests, and here the difference between two groups of post-Communist countries is interesting. In the Central European countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary) and the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), the ideas of rapid privatisation, price liberalisation and, as a whole, “shock therapy” were accepted almost unanimously. This was seen as a way to break with the past and to mimic Germany and the other core EU countries. For instance, when analysing the new geography of money and especially the subordination of monetary sovereignty, B. Cohen cites Estonia as an example:

19For Argentineans, weary of hyperinflation and humiliating succession of worthless money, the Convertibility Plan became a source of national pride […] Similarly, Estonians understood the link of their newly-created kroon to Germany’s mark not as an admission of weakness but as an assertion of social identity – not just borrowing credibility from a respected foreign central bank but more as an act of faith in their resurrected state. The virtues of Estonian’s currency board “are now so ingrained they’re a religion,” a foreign adviser has been reported to say. To change the peg “would be seen as an unpatriotic thing”. (Cohen, 1998, 122).

20Similar observations are made by J. Blanc and JF Ponsot when studying the sociological aspects of the Currency Board introduction in Lithuania (Blanc and Ponsot, 2004, Blanc, 2007). These authors demonstrate the strong political meaning of choosing this particularly rigid monetary regime, considering it to be a definite commitment “to return to the West”.

- 6 We must mention that neither the neoclassical theory nor the political economy of socialism had ins (...)

21Inversely, in the Balkan countries, there was strong resistance, even rejection, of these ideas. Interestingly, this refusal of liberal ideas came not from realising the complexity institutional understanding of the transition, but was instead inspired by retrograde Soviet-style Marxism, which deliberately or naively defended its ideas and theoretical concepts.6 Most economists from the Balkan countries defended the role of the state/government and justified the socialisation of losses and the accumulation of debt. This fit perfectly with the interests of the groups that had “drained” and privatised the public, “all-people’s” property.

- 7 See Balcerowicz (1995, 2013).

- 8 This project, by the way, proposed the introduction of the Currency Board (another option was free (...)

22On the whole, whereas the Central European countries made key liberal reforms and had liberal reformers in power (L. Balcerowicz,7 L. Bokros, V. Klaus, M. Laar, and others), the Balkans missed such opportunities. One revealing instance was Bulgaria’s refusal to adopt the radical liberal reform project suggested by the US Chamber of Commerce (known as the Rahn-Utt Project, 1990), in which many Bulgarian economists participated, mostly from the Bulgarian Communist Party!8

Figure 2: Interests, Economic Policy Tools, and Economic Discourse

23Following the model illustrated in Figure 2, until 1996/1997 (i.e. the period of primitive accumulation of capital, described above), the leading interest groups targeted the state. During that period, the external, foreign actors still had a subordinate impact. In order to capture the state/government functions, domestic actors needed economic policy that would allow greater government discretion and more opportunity for redistribution. Such discretion consisted of having complex and opaque fiscal policy, privatisation methods, exchange rate determination, refinancing by Central Banks, etc. As an illustration, during the period 1994-1996, a high-level management group was formed at the Bulgarian National Bank. This group was in charge of monetary policy instruments (mainly bank refinancing, daily exchange rate intervention, etc.), but in fact, it served private groups. Some members of this management group accumulated and transferred abroad large amounts of funds.

24Mobilising economic discourse for the purposes of justifying this type of discretionary state policy came as a logical step. Economic discourse consists of mixing certain economic theories, models, ways of reasoning, etc., that justified the interests of the main actors and protagonists. During this period, the range of theories and ideas claiming an active state role (a mixture of Marxism and Keynesianism) were leading. Discretionary government policy was justified by Keynesian theories and textbooks. Government was seen as the main driver of privatisation. Liberal and market ideas in a classical form had a place only where they were advocated by foreign intellectuals or those scholars linked intellectually to the Western community or financed by Western academic foundations.

25A set of macroeconomic indicators – in particular economic growth, inflation, the budget deficit, budget expenditures, public debt, non-performing loans and money supply growth – could indirectly illustrate the described redistribution processes and the crony economy in the first period of transition (see Appendix 1). The periods differ slightly for the groups of countries analysed, depending on when crisis occurred in each country. The period covered for Bulgaria and Romania is 1996/1997, for Albania and Serbia 1990-1999/2000 (Yugoslavia had gone through a crisis in the early 1990s, particularly in 1991-1993, which cannot be seen on the charts). In the first transitional period, which began after the end of the planned economy, huge public debts were accumulated (especially in Bulgaria, Albania and Serbia), dominated by domestic public debt. Due to a lack of structural reforms, delays in privatisation, disorganisation and high redistribution of wealth, there was negative economic growth. Losses in the public sector, due to its inefficiency, were passed on to the banking sector, which accumulated significant non-performing loans (about 60% in Romania in 1998 and about 80% in Albania in 1997). Public finances were also on a poor footing due to high expenditure and huge public debts. The central banks monetised the losses in the real and public sectors, leading to an increase in the money supply (in 1997, about 350% year-on-year growth in broad money in Bulgaria).

26The late-1990s crises, which were the logical end of the accumulation and monetisation of debts, as well as the gigantic redistribution of property and resources, required a radical change in the economic policy model, as well as in economic discourse and theoretical reasoning. The majority of individuals and groups desired a stable monetary system (as in Western Europe), with understandable and visible policy rules. This meant a lack of policy discretion. In fact, discretion had been compromised in the initial transitional period. The establishment of new rules was made easier by the fact that the accumulated debts had been cleared by hyperinflation, depreciation of the national currency and financial sector crisis.

- 9 The mechanisms of forming this consensus are analysed from a political economy point of view in Nen (...)

27Two institutional mechanisms became dominant and justified the new anti-capture economic policy model. Firstly, a consensus was built on the need for radical stabilisation in the monetary and financial system.9 The monetary regime became the key anchor for the normalisation of state functions and for thwarting the predatory actions of the national private groups.

- 10 The accumulation of foreign reserve under the Currency Boards is considered by foreign creditors an (...)

28Summarising the consensus on the Currency Board being introduced in Bulgaria, for example, we could stress that after the hyperinflation and deep banking crisis, this consensus arose out of a convergence in the interests of the main groups: internal creditors (mainly households), external creditors (IFI, IMF) and debtors (the government and crony sector). Households, for instance, preferred a stable currency after experiencing huge losses on their savings. External creditors prized Currency Boards for their capacity to guarantee foreign debt payments (Currency Boards require considerable amount of foreign reserves).10 The group of crony debtors, after being freed from their debt following hyperinflation, and after successfully participating in the privatisation of the most promising assets, needed stability for their businesses and property.

29The second mechanism that appeared almost simultaneously in Bulgaria and Romania was the start of negotiations for EU membership. This was an external stabilising and normalising anchor. This kind of geopolitical fixing is still present in all Balkan countries, albeit to varying extents.

30In short, a social anchor is an institution, social regulation, focal point, or anything else, that coordinates and stabilises the expectations, interests, ideas, and behaviour of the leading social groups and individuals. Its function is not only to increase social cooperation, to build trust, but also to reduce uncertainty, and as a result, transaction costs. By their very nature, anchors could be internal to certain social communities (e.g. within a country), or external to them. Anchors could appear spontaneously, as a result of a continuous interaction between the actors, or as a result of powerful imposition or force.

- 11 See also Nenovsky et al. (2012), Nenovsky and Karpouzanov (2014), Ialnazov (2003).

31In our case in point, the two anchors (the monetary regime and EU integration) followed interesting complementary and contradictory dynamics. The hypothesis that the government dynamics of the Balkan countries (and the Eastern European countries as a whole) can be attributed to the interaction of the two above-mentioned anchors has been studied before (Nenovsky and Ialnazov, 2011, Nenovsky and Villieu, 2011).11

32Monetary instability or stability always goes hand in hand with social instability or stability. In the beginning of the post-Communist transformation, two groups of post-Communist countries could be outlined. They opted, respectively, for fixed or floating exchange rates, i.e. for an external or internal monetary anchor. Basically, the reforms in the countries with fixed (or close to fixed) exchange rates turned out successful, and the economies of these countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia) managed in one way or the other to minimise the crony processes (Balcerowicz, 1995, Nenovsky, 2009, Vucheva, 2001). Later, after the 1990s crisis, these countries moved to inflation targeting and more or less floating exchange rates.

33On the other hand, the second group – the Balkan countries – opted for managed floating exchange rates, maintained discretionally by the Central Bank (during this period, monetary base targeting was used).12 This led to massive speculation on the exchange market, and to generalised exchange rate and price volatility. The exchange rate and inflation became essential mechanisms for redistribution and enrichment. The 1990s crises put an end to the managed float regime. A conservative, externally-oriented monetary regime was adopted. This regime was dominated mostly by external interests, mainly foreign creditors (in fact, the initiators for the monetary regime change). This kind of externally-oriented and static monetary regime includes the Currency Boards in Bulgaria (1997) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1997) (see Hanke, 2012, Kovacjevic, 2003), as well as the introduction of the D-Mark and later the euro as the official currency in Montenegro (1999/2001) and Kosovo (1999/2001). It also includes the de facto fixed exchange rate in Romania (after 1996/1997) and Albania (after the collapse of the financial pyramids in 2000) (for more information, see Sevic ed., 2002, Fabris et al., 2004, Frommel and Schobert, 2006, Jarvis, 2000).

- 13 The Brazilian experience from 1995 was similar when the Unidade Real de Valor (Unit of Real Value) (...)

34Following the same logic of monetary change, we could point out the currency reform in Yugoslavia. There, after a continuous hyperinflation, Dragoslav Avramovich (a former employee of the World Bank and an American citizen) introduced a parallel monetary unit – the new dinar (interestingly, Avramovich was inspired by the NEP experiment in Soviet Russia, and he discovered the idea reading an old book). The new dinar was pegged to the D-Mark at 1:1, and circulated simultaneously with the old one (Rostovsky, 1995, Mladenovic and Petrovic, 2000).13

- 14 It is interesting to draw a historical parallel, when in the past attempts at monetary stabilisatio (...)

35As a whole, the restrictive and conservative monetary regime created hard budget constraints, and coincided with low budget deficits (and even a surplus in the case of Bulgaria). With the complete refusal to drive monetary policy and to act as a lender of last resort (LLR), the presence of foreign banks and attraction of foreign capital was considered to be the inevitable solution. Soon, the penetration of foreign banks had become a notable fact. The presence of foreign banks also had political economy explanations, insofar as the foreign creditors were the main inspirers of the Currency Board introduction.14 The complete domination of the Bulgarian banking sector by foreign banks and capital (the situation was similar in the other Balkan countries) was never called into question. Every criticism of foreign banks was viewed as an attack on Bulgaria’s future as a European and civilised country.

- 15 This is explained in great detail in Nenovsky and Rizopoulos, 2003. As Yugoslavia collapsed, simila (...)

36Following the model presented in Figure 2 (illustrated again by Bulgaria), in this second period, the external actors (mainly foreign creditors, private banks and IFIs) dominated, and in coalition with the local creditors (households) and debtors (the government, the crony sector), they imposed a model of economic policy favourable to them. For instance, after the deep crisis (hyperinflation, exchange rate depreciation, banking collapse, and default on foreign debt), Bulgaria was forced to sign an IMF agreement in order to avoid social and political chaos.15 The new, post-crisis, policy framework included a stable currency, small government, lack of discretion, as well as accelerated privatisation. The Currency Board and restrictive fiscal policy were perfect instruments for this purpose.

37A fast and radical change in the economic discourse also occurred. The liberal theories, mostly the Austrian school, monetarism (the libraries were filled with translations of F. Hayek, L. Mises, M. Rothbard, A. Rand and M. Friedman), the principles of monetarism and supply side economics (the Laffer curve, flat tax, vouchers in education and health sectors), etc., became firm theoretical elements in economic education, economic publications and economic discussions in general. Any deviation from this line of discourse was rejected and ridiculed as retrograde, and as extremely anti-European and anti-Western.

38The decision of the leading European countries (chiefly Germany and France) on EU expansion towards the Balkans was the second anchor, geopolitical in nature. It helped normalise the state/government, and at least in the beginning, liberated it from the vested interests. Chronologically, the accession started initially for Bulgaria and Romania, later for Croatia, and is an ongoing process in different stages for Macedonia, Albania and Serbia. In Bulgaria and Romania, EU membership became a general project, a principal national goal. By its nature, the pre-accession process was related to hard budget constraints, including fulfilment of a number of indicators of economic, institutional and legal convergence. It consisted of opening and closing a number of pre-accession chapters on the main membership topics (35 in all). These chapters aimed to develop the institutional framework and generally the practices of good public governance, and to bring them closer to European levels. The final point was to reach the acquis communautaires.

- 16 The lower the index (on a scale of ten), the higher the perception of corruption. Interestingly, af (...)

39At that time, the EU anchor had not only a disciplinary effect, but also a credibility one. These two EU effects combined with the discipline and trust coming from the newly-established monetary regime, leading to a significant decrease in cronyism. For example EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) governance indices, as well as corruption indicators, improved considerably (the Corruption Perception Index published by Transparency International rose from 2.9 in 1998 to 4.1 in 2007).16 To a great extent, the state had restored its general functions. Practically all major economic actors worked in favour of EU integration, and a large consensus was built on the necessity to move to a normalisation of public practices in line with western ones.

40However, the story does not end here. The initial effect soon vanished. In Bulgaria and Romania (and other Balkan countries will most probably follow the same experience), this successful stage was relatively short-lived; it continued during the pre-accession period, until full membership in 2004/2007. With full membership, things have changed for the worse. Since then, we have had all the reasons to state that there are trends towards a new privatisation and state capture.

41The answer to how this happened can be found in the dynamic interaction between the two above-mentioned anchors: monetary and European.

- 17 Recently, similar ideas are developed by Hans-Werner Sinn in more general terms, in Sinn (2014).

- 18 EU funding was practically seen only positively, and its redistribution and state capture effects w (...)

- 19 Corporate Commercial Bank (Centralna Corporativna Banka) was a Bulgarian bank. According to officia (...)

42In short, soon after EU accession in 2007, the disciplinary effect of the European anchor was undermined. In fact, EU membership created many guarantee and “insurance” mechanisms that led to an under-pricing of risk and a resurgence of moral hazard behaviour.17 Capital inflows and EU funds became sources for profiteering, and in the best case, went to consumption and luxury goods.18 Different “capturing” groups and coalitions of groups rapidly appeared all around EU funds and foreign capital inflows. All such groups were close to the government or were inside the government itself. Agriculture was an especially actively targeted field for capture, as the funds were considerable. As a result, the Ministry of Agriculture and the so-called “State Fund Agriculture – Paying Agency” (in the case of Bulgaria) became extremely coveted and powerful. In the banking sector, new banks emerged that were specialised in capture, and the existing ones were directed towards capturing, too (the Corporate Commercial Bank in Bulgaria is a good example)19.

43Lending increased rapidly in all countries analysed (see Appendix II). Debts began to accumulate substantially again (private debt in Bulgaria, public debt in Romania). Bad loans exploded. Normally, such dynamics are incompatible with the functioning of a hard monetary regime and fixed exchange rate, because they lead to an exchange rate crisis. Curiously, whether on purpose or not, policymakers never seriously considered the fact that fixed exchange regimes and foreign guarantees attract capital flows that could be dangerous at a later stage.

- 20 See Nenovsky and Villieu (2011), Nenovsky et al. (2012), and Nenovsky and Karpouzanov (2014).

- 21 See the original analysis of the types of state capture (corporate versus party), suggested by Inne (...)

44The literature has discussed in great detail the mechanisms of moral hazard and its specifics in Bulgaria and Romania.20 What is important here is the fact that the monopolisation, redistribution processes and corruption have increased again. This fact has been noted by many researchers. For example, the Corruption Perception Index’s “Doing Business” indicators have deteriorated (see Appendix III). In some respects, events in Bulgaria and Romania have shown a new stage of state capture. This stage is also visible in the other former Communist countries that are now EU members.21

45The post-Communist transformation can be split into two major stages. The first period was primitive accumulation of capital and property, “privatised state”. Economic discourse followed, legitimising leading interests and policies. Accumulation of debts and losses led to a crisis in the late 1990s. During the crisis (inflation and hyperinflation), debts were cleared, the redistribution of “Communist” wealth ended, and foreign players became stronger.

46Then, the second stage began – state de-privatisation and de-capturing. The need arose for a new type of policy, based on clearly-defined policy rules and restricted government. Hard monetary regimes were leading tools. Liberal ideas (monetarism, conservative public finance management, “pure” market, etc.) quickly gained ground. At the same time, a second geopolitical anchor appeared: the prospect of EU membership. As a whole, the pre-accession processes had a strong disciplinary and credibility impact on the national economies (Bulgaria and Romania in the early 2000s, and Serbia and Albania today).

47The full membership of Bulgaria and Romania almost coincided with the beginning of the current crisis. In the Balkans, this crisis was part of the European one, but with its own specificities. These were mostly related to the increase in moral hazard processes, greater corruption and higher luxury consumption. Old and newly-formed groups again captured economic policy tools. These groups were mainly linked to EU funding and to foreign economic interests, banks, etc.

48The trend in the economic discourse is interesting. The current crisis was initially interpreted from a liberal stance. For example, it was claimed that the main Central Banks’ policy caused speculative bubbles (because of time inconsistency in monetary policy, or vested interests), that the financial markets were badly regulated, or even that the EU bureaucratic model was the primary cause.

49With time and as the problems began to increase, however, things have changed. For instance, in Bulgaria, the collapse of one large bank (Corporate Commercial Bank, a symbol of cronyism) led to a rapid deterioration in public finances (from a near surplus to a projected 3.7% deficit in 2014). This logically led to a shift in the economic discourse towards more government involvement. Paradoxically, the new crony groups need more and more discretionary economic policy, i.e. active policy instruments, to help and serve their interests. There is increasing talk of the important role of the state and the need to stimulate the national economy. Curiously, the list of those that lost Corporate Credit Bank deposits includes a club called “Libertarians”, which held deposits of around EUR 400,000 (a considerable sum for the scale of Bulgaria). This club is specialised in translating liberal authors. Not a single name can be found on its website – a strange anonymity.